Provider FAQs: Technology, quality, & scientific contribution

Sequencing methodology

- What molecular methods does Invitae use?

Clinical genetic testing requires carefully constructed methods to thoroughly interrogate genes of medical importance. Invitae’s clinical diagnostic laboratory, which is accredited by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified, offers multi-gene panels and exome sequencing for diagnostic and genetic risk testing purposes. We also offer supplementary RNA analysis for specific oncology panels. These molecular assays—almost exclusively based on next-generation sequencing—report sequence changes and deletion/duplication events in coding exons, introns, splice sites, and other regions known to potentially harbor pathogenic variants. See the FAQs below for more details about the technology Invitae uses for multi-gene panels, exome sequencing, and supplementary RNA analysis.

Genetic changes such as large insertions/deletions, small copy number variants, variations in repetitive regions, and mosaicism can be particularly challenging to detect by standard next-generation sequencing due to limitations in assay chemistry, sample-to-sample variability, or bioinformatic processes. Invitae has addressed these challenges through extensive laboratory research and development to improve all of our molecular methods. We have also developed bioinformatic tools specialized in detecting specific types of challenging variants.

For a subset of clinically significant findings that are technically challenging or do not meet our stringent quality metrics for next-generation sequencing, orthogonal methods such as PacBio sequencing, Sanger sequencing, array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) are used to confirm our results.

Learn more

- Read blog post—How Invitae detects challenging genotypes

- Watch webinar—Challenging variant types detected by next-generation sequencing and their contribution to monogenic disease

- Download white paper—Confirmation for clinical genetic testing

View peer-reviewed publications - Patterns of mosaicism for sequence and copy-number variants discovered through clinical deep sequencing of disease-related genes in one million individuals

- Scalable detection of technically challenging variants through modified next-generation sequencing

- One in seven pathogenic variants can be challenging to detect by NGS: an analysis of 450,000 patients with implications for clinical sensitivity and genetic test implementation

- Prevalence and properties of intragenic copy-number variation in Mendelian disease genes

- A rigorous interlaboratory examination of the need to confirm next-generation sequencing: detected variants with an orthogonal method in clinical genetic testing

- What does Invitae’s multi-gene panel testing include?

Multi-gene panel testing is increasingly recognized for its utility in a variety of clinical scenarios. It not only reduces the cost of genetic testing, when compared with sequential testing of single genes, but also shortens the diagnostic journey for many patients. This approach has been shown to provide comprehensive germline genetic information to help inform care for cancer patients diagnosed with a variety of tumor types.1,2

Invitae's multi-gene panel testing includes simultaneous sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis for most genes on the ordered panel using next-generation sequencing technology. If clinically indicated, a single gene or a small subset of genes from any of the panels can also be analyzed in isolation with the same level of coverage and quality.

Sequencing generally covers clinically important regions of each gene including coding exons, 10 to 20 base pairs of intronic sequence on either side of the coding exons, and select noncoding variants. Invitae’s deletion/duplication analysis determines copy number at a single exon resolution at virtually all targeted exons. However, in rare situations, single-exon copy number events may not be analyzed due to inherent sequence properties or isolated reduction in data quality. For some genes (see test catalog), analysis may extend to the promoter region, include additional intronic variants, or be limited to targeted variants or exons.

Invitae’s next-generation sequencing panels generate an average depth of coverage of 300x to 500x per assay, meaning that 300 to 500 sequence reads are available, on average, at any DNA nucleotide position in the reportable range. Importantly, we strive for 50x coverage at any given position to detect a genetic variant.

Learn more

Search for a specific gene or panel test—Invitae test catalogReferences

1. Samadder J, et al. Comparison of Universal Genetic Testing vs Guideline-Directed Targeted Testing for Patients With Hereditary Cancer Syndrome. JAMA Network. 2021;7(2):230-237.

2. Reviewed in Esplin E, et al. Universal Germline Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes in Patients With Solid Tumor Cancer. JCO Precision Oncology 6, e2100516(2022). - Does Invitae offer deletion/duplication analysis?

Yes, Invitae’s panel tests detect deletion/duplication events. Any cases in which specific genes and exons are excluded from analysis are described in our test catalog.

For more information, please see the following FAQs:

- How has Invitae validated its molecular methodologies?

- What molecular methods does Invitae use?

- What does Invitae’s multi-gene panel testing include?

- How does Invitae exome sequencing work?

- How does Invitae select which genes to include on multi-gene panels?

Our team of board-certified medical geneticists, board-certified genetic counselors, laboratory directors, and PhD scientists works together to carefully curate each gene and the variant spectrum associated with disease so that genetic testing delivers clinically relevant results:

- Invitae's team of PhD scientists and board-certified genetic counselors extensively reviews the literature and public databases for each gene.

- Genetic disorders associated with each gene are analyzed, including their penetrance, inheritance patterns, and the nature of known pathogenic variants.

- Each gene's molecular characteristics are defined, including known transcript isoforms, detailed gene structures, and challenging regions to assay.

After review, genes are organized into panels that help you order the genetic test that matches your patient's clinical presentation.

Learn more

Search for a specific gene or panel test—Invitae test catalog - How does Invitae exome sequencing work?

Exome sequencing is typically ordered when a patient presents with complex symptoms that have a suspected genetic etiology or when the patient has undergone other forms of testing with no informative results.

Rather than limiting analyses to one or several genes, exome sequencing can evaluate almost all protein-coding genes in the human genome (>18,000 genes in a single assay) and detect single nucleotide variants, small insertions and deletions and intragenic copy number variants. Invitae's exome analysis utilizes advanced next-generation sequencing technology.

Genomic DNA obtained from the submitted sample is prepared for sequencing using a PCR-free method and sequences the entire genome. While the underlying technology sequences the whole genome, analyzed targets include exons +/-20bp of flanking region.

Invitae provides case-level reanalysis at no additional charge every six months (for a period of three years from the exome report date) so that the full exome can be reconsidered in light of new public or patient information. In addition to providing full-exome reanalysis, Invitae remains committed to providing variant-level reevaluation when new data become available.

High-powered software

Our MoonTM software tool rapidly and reliably analyzes the exome. Powered by machine learning, Moon weighs clinical and genetic information to identify the variants that are most likely to be relevant to each patient’s case.Moon is supported by an expertly curated gene-disease database called ApolloTM, which leverages text mining algorithms to stay up to date. An internal study of 150 previously solved exome cases showed that Moon correctly identified more than 97% of causative variants in less than two minutes per exome.1 Integrating this tool into the interpretation of our sequence data allows us to bring the benefits of comprehensive clinical sequencing more quickly to more patients while maintaining exceptional accuracy and reproducibility.

Learn more

- Download white paper—Invitae exome interpretation: Leading with science and innovation to bring exomes to scale

- Download poster—Repeated exome reanalysis is most impactful after two years and the majority of new findings are in neurodevelopmental genes

- Browse Invitae’s offerings—Exome test options

- Watch webinars

Reference

1. O’Brien TD, et al. Artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted exome reanalysis greatly aids in the identification of new positive cases and reduces analysis time in a clinical diagnostic laborator. Genet Med. 2022 Jan;24(1):192-200. - Does Invitae offer RNA analysis?

Invitae uses RNA analysis to supplement results from our hereditary cancer multi-gene panel testing. RNA analysis is not a diagnostic test, but rather provides information about the functional effects of DNA variants. This information is used to help classify variant(s) of uncertain significance (VUS) and detect novel DNA variants deep in the intronic regions of 56 hereditary cancer genes.

To perform this analysis, patients’ RNA is extracted from a blood sample and used to create complementary DNA (cDNA) that can be sequenced with standard next-generation sequencing protocols. The data from RNA analysis are then used to identify changes in splicing patterns that are specifically associated with variants identified by DNA panel testing. While our DNA panel testing for germline cancer genes is tuned to identify variants in an intron within 20 base pairs of a coding exon and selected intronic regions known to harbor pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants, splicing changes observed with RNA analysis can help identify DNA variants throughout the entire intron, further extending the reportable range for disease-causing variants.

Research from more than 69,000 individuals who underwent simultaneous DNA and RNA sequencing for hereditary cancer at Invitae suggests that RNA analysis can help provide definitive results for a small but important group of patients. Among all individuals tested, data from RNA analysis helped change the classification from VUS to benign/likely benign or pathogenic/likely pathogenic in 2.2% of individuals and helped identify deep intronic pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in approximately 1 in 1,670 individuals.1

Learn more

- Download poster—Yield of integrated DNA and RNA analysis of hereditary cancer associated genes based on cancer diagnosis.

- Read peer-reviewed publication—A Systematic Method for Detecting Abnormal mRNA Splicing and Assessing Its Clinical Impact in Individuals Undergoing Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes

Reference

1. Heald B, et al. Oral presentation session #C11. Presented at the 42nd NSGC Annual Conference; October 17, 2023; Chicago, IL. - How has Invitae validated its molecular methodologies?

To demonstrate that Invitae’s next-generation sequencing analysis provides the high-quality results you are accustomed to, all of our molecular methods have been validated in compliance with College of American Pathologists (CAP) and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) standards. Additional studies have evaluated the performance of select methods in a variety of real-world contexts:

Multi-gene panel testing for breast and ovarian cancer genes

A study comparing Invitae’s hereditary cancer panel test to traditional BRCA1 and BRCA2 tests in more than 1,000 patients was undertaken in collaboration with the Stanford University School of Medicine and Massachusetts General Hospital. The results, published in the Journal of Molecular Diagnostics, demonstrated over 99.9% analytic sensitivity and specificity for Invitae’s next-generation sequencing multi-gene panel compared with traditional genetic test results for both sequence alterations and intragenic deletions/duplications.To learn more, please read our white paper Invitae hereditary cancer analytic validation.

Detection of deletions and duplications

Invitae’s next-generation sequencing approach for detecting intragenic deletion/duplication events (i.e., copy number variants) uses a custom-built set of computer algorithms in conjunction with optimized biochemical laboratory methods. A validation study among nearly 1,200 samples showed >99.9% sensitivity and specificity in detecting deletions and duplications in genes involved in cancer, cardiology, neurology, pediatrics, and other conditions and clinical areas. A subsequent study evaluating deletions and duplications in 1,507 genes in more than 143,000 patients referred to Invitae for genetic testing found that they were overrepresented among clinically significant variants. The study, published in the journal Genetics in Medicine, highlighted the importance of broad implementation of our high-resolution detection method.To learn more, please read our white paper Detecting deletions and duplications using next-generation sequencing and our peer-reviewed publication Prevalence and properties of intragenic copy-number variation in Mendelian disease genes.

Sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis of exons 12–15 of PMS2 (Lynch syndrome)

An appreciable proportion of cases of Lynch syndrome are caused by variants in the PMS2 gene. Gene conversion involving a sequence spanning exons 12 through 15 of PMS2 and a nearby copy of a similar sequence (i.e., partial PMS2 pseudogene) can complicate detection of disease-causing variants. Invitae’s next-generation sequencing approach for evaluating exons 12–15 of PMS2 is a two-step process for sequence variants and a three-step process for intragenic deletions and duplications. Validation of both processes demonstrated 100% accuracy, reproducibility, and analytical sensitivity and specificity.To learn more, please read our white paper Sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis of exons 12–15 of PMS2 using next-generation sequencing, our blog post Leading with quality: Full PMS2 testing, and our peer-reviewed publication Scalable detection of technically challenging variants through modified next-generation sequencing.

Diagnostic testing of SMN1 and SMN2 (spinal muscular atrophy)

Validation of Invitae’s genetic testing approach for spinal muscular atrophy, using next-generation sequencing with a customized bioinformatics solution designed for simultaneous sequence and copy number analysis, showed 100% sensitivity and specificity for SMN1 and SMN2 copy number. A separate study, published in the journal Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers, showed that integrating this approach into a multi-gene neuromuscular panel allowed comprehensive assessment of a wider spectrum of variants in individuals with suspected spinal muscular atrophy or other neuromuscular indications.To learn more, please read our white paper Invitae’s approach to diagnostic testing of SMN1 and SMN2 for spinal muscular atrophy and our peer-reviewed publication Scalable detection of technically challenging variants through modified next-generation sequencing.

Comprehensive analysis of AGG interruptions in FMR1 (fragile X syndrome)

Invitae developed and validated a next-generation sequencing assay and customized bioinformatics solution to determine the location and number of AGG interruptions within the CGG repeat tract of the FMR1 gene. When results from our method were compared with those from an alternative established approach, concordance was 100% for AGG genotypes, demonstrating the high accuracy and precision of Invitae’s method. - What cytogenetic methods does Invitae use?

Unlike molecular methods, which are designed to detect variation at the DNA sequence level, our chromosomal microarray analysis detects variation at the larger chromosomal level. For more information please see the test catalog.

- How has Invitae validated its chromosomal microarray analysis?

To demonstrate that Invitae’s chromosomal microarray analysis provides the high-quality results you are accustomed to, our array methods have been validated internally in compliance with College of American Pathologists (CAP) and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) standards.

Confirmation

- Does Invitae confirm variants?

For a subset of clinically significant findings that are technically challenging or that do not meet our stringent quality metrics for next-generation sequencing, orthogonal methods such as PacBio sequencing, Sanger sequencing, array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) are used to confirm our results.

- Which variants get confirmed?

We have a robust system in place for identifying which variants require confirmation. Our confirmation rules for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels (small insertions and deletions) are as follows:

We confirm a variant if:

- It does not meet stringent NGS quality metrics, and/or

- It is located in a known challenging region for next generation sequencing, and

- It has been classified as pathogenic; likely pathogenic (disease causing); or, in some cases, a variant of uncertain significance.

We do not confirm a variant if:

- It meets stringent quality metrics that have been shown to indicate high-accuracy NGS results.

- It has been classified as benign or likely benign, or in most cases for a variant of uncertain significance

- How does Invitae confirm single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels?

Our confirmation for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels is performed with Sanger sequencing or PacBio sequencing, depending on the need. For STAT tests that require a fast turnaround time, we confirm with Sanger sequencing exclusively. All of our confirmation methodologies, including PacBio sequencing, have been validated.

- How does Invitae confirm copy number variants (CNVs)?

Invitae confirms reported copy number variants (CNVs) by performing MLPAseq or aCGH with a custom-designed, exon-focused microarray. These are the industry standard techniques for these events.

An exception to our current CNV confirmation policy is for PMS2. A combination of MLPAseq and long-range PCR PacBio data is used for exons 12-15 of this gene to disambiguate genic events from pseudogenic events. Learn more in our PMS2 white paper.

Variant classification and reporting

- How does Invitae classify variants? And what’s Sherloc?

Invitae is dedicated to utilizing the latest variant classification techniques to better understand the clinical impact of each variant identified by our genetic tests. We have built and published our own variant classification framework called Sherloc, which builds on the initial American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) classification framework and is an industry leader among clinical genetic testing laboratories.1 The point-based Sherloc system supports objective and systematic use of various lines of evidence, including data from our Invitae Evidence ModelingTM platform and RNA analysis when appropriate, to ensure consistency and accuracy in classifying individual genetic variants as pathogenic or likely pathogenic, as benign or likely benign, or as variant(s) of uncertain significance (VUS). The field of genetics is constantly evolving, so if new evidence on a variant becomes available, we review our variant classification and, if indicated, will reclassify it and may issue an addended report to the ordering clinician.

Learn more

- Read the Genetics in Medicine paper—Sherloc: a comprehensive refinement of the ACMG-AMP variant classification criteria

- Watch webinar—Variant interpretation 101: Back to basics

- Read blog—The art (and science) of variant interpretation

Reference

1. Invitae, data on file. - What is the Invitae Evidence Modeling™️ platform?

The Invitae Evidence ModelingTM platform is a platform developed at Invitae for the systematic development and testing of machine-learning (ML) variant prediction models. These models help our team of clinical experts generate evidence for variant classification (VC) at scale. The platform enables standardized evaluation of the probability of pathogenicity or lack thereof for a given variant, which is then incorporated in our variant classification system in addition to all of the other evidence we have for that variant. The platform helps us reduce the number of patients who receive inconclusive results containing variant(s) of uncertain significance (VUS).

The Invitae Evidence Modeling platform ML models are largely trained and validated in a gene specific manner and only models that meet our stringent quality thresholds a given gene are incorporated into our variant classification system. Adding this information to the other evidence already available in Sherloc has the potential to push a VUS into the benign/likely benign or the pathogenic/likely pathogenic classifications. As of October 2023, the incorporation of evidence from the modeling platform has helped over 390,000 variants reach definitive classifications, impacting over 545,000 patients across all of our clinical areas.1

Learn more

ACMG 2024 Oral Presentation

Webinars

- The benefits and limitations of artificial intelligence and machine learning in clinical genomics and variant interpretation

- Innovations in variant interpretation: the role of cellular evidence modeling

- Improving variant classifications in Lynch Syndrome genes through functional data generation and clinical data modeling

- Innovations in variant interpretation: learning from over 8 years of variant reclassifications

White papers

Reference

1. Invitae, data on file. - How does Invitae help resolve variant(s) of unknown significance (VUS)?

Invitae routinely partners with clinicians to help minimize uncertainty in genetic testing for patients. For example, to help resolve variant(s) of uncertain significance (VUS), Invitae offers follow-up testing for select family members of patients previously tested at Invitae. Our follow-up testing program is available when testing additional family members may clarify the relationship between a specific variant and a genetic condition. Although participation in this program may not result in an immediate reclassification of a VUS, reclassification may still occur after multiple families with the same variant have been tested or other types of evidence emerge. If a variant is reclassified, Invitae may issue an addended report with the new interpretation for all individuals who were tested at Invitae and found to have the variant.

Invitae also works to resolve all VUS on a regular cadence as more information emerges about particular genes and variants, including clinical data, functional data, and improvements in predicting pathogenicity. This reanalysis of VUS removes burden from the patient and provider to request this type of reevaluation. When reanalysis leads to changes in variant classification that are clinically significant, updated results are delivered to the healthcare providers.

Invitae also uses innovative approaches to help reduce VUS, including generation of large scale functional datasets called multiplex assays of variant effects (MAVEs) that examine the impact of VUS on protein function and/or gene expression using cellular based assays. Additionally, we offer RNA analysis for hereditary cancer testing, to examine the impact of VUS on splicing. Additionally, as of October 2023, the incorporation of evidence from the Invitae Evidence ModelingTM platform has helped over 390,000 variants reach definitive classifications, impacting over 545,000 patients across all of our clinical areas.

- What does an Invitae report include?

For our next-generation sequencing panels, scientists at Invitae review each patient’s genetic findings and summarize them into a clinical report. Each report is then reviewed and signed by a board-certified medical geneticist or pathologist and delivered via portal or fax, depending on the preference of the ordering clinician. Our clinical reports highlight the most important findings and provide more information about the specific genetic tests ordered and what the results might mean for patients, their families, and their medical care. Invitae follows American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines for structuring the reports.

Each report includes:

- Results: High-level results of the genetic test (positive, negative, or clinically inconclusive), genes in which any genetic variants were identified, and disorders that may be associated with those variants.

- Next steps: Considerations for family members and professional guidelines for managing conditions associated with the result, if relevant.

- Clinical summary: A detailed explanation of the relevance of the genetic result to the patient based on his or her clinical and family history.

- Variant details: A summary of the evidence and logic used to justify the clinical classification of each variant.

- Genes analyzed: A complete list of genes analyzed in the test.

- Methods: A description of the test processes used.

- Limitations: Limitations of the assay.

Because genetic testing can have health implications for entire families, Invitae offers follow-up testing for all first-degree relatives of patients who receive a positive result (i.e., findings of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant). Invitae also offers follow-up testing to help resolve variant(s) of uncertain significance (VUS) in our test results. If the classification of any variant on your patient’s report changes, an addended report may be issued.

Learn more

View sample next-generation sequencing report—Invitae diagnostic testing results - Do you copy from or base your classifications on ClinVar?

No. All of our classifications are made independently according to our Sherloc framework which is based on the ACMG/AMP guidelines for variant classification and is peer-reviewed and published.1 We don’t copy other labs’ classifications at face value. Our team of experts examine all of the available evidence for a given variant and classify the variant based on this evidence.

We are active participants in the NIH-funded Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen), which is helping define the clinical relevance of genes and variants. Learn more about these efforts here.

We are also transparent about what evidence goes into our classifications and what additional information we would need for a more definitive classification. and have open dialogues with other clinical laboratories to help resolve any differences.

We are the leading submitter to ClinVar. Review our ClinVar submissions here.

Reference

1. Nykamp et al. Genet Med. 19, 1105–1117 (2017). - Why do you only need one variant to determine whether a gene causes a specific disease?

If at least one pathogenic variant exists in a gene, any variant in that gene could potentially be pathogenic. Conversely, if there are no conclusively pathogenic variants in a gene, we can't be sure that the gene causes disease. While reviewing the evidence for each variant in each gene is a time-consuming process, we want to make sure that the evidence meets our own high standards.

To help move the industry forward, we are active participants in collaborative efforts to identify which genes and variants cause disease. One of these projects is the ClinGen Gene-Disease Validity project, though their scope is slightly different than Invitae’s. While the ClinGen project aims to figure out which genes cause which disease, the project is also interested in comparing the relative amounts of available information for each gene.

- How does Invitae find and evaluate literature evidence?

Invitae finds scientific articles by using several complementary methods. The primary method is a natural-language processing algorithm that automatically searches through hundreds of thousands of scientific articles and only displays literature to our team of experts that likely contains information about the variant. A second method searches publicly available databases, such as ClinVar, to find additional articles. Finally, the PhD scientist or genetic counselor manually reviews each article. During the review process, the they may identify other materials. In our experience, our natural-language processing algorithm provides significantly more information than relying on manual searches or references available in public databases.

Once we’ve found the literature, a PhD scientist or genetic counselor look at all of the available evidence and reads through each article to identify specific information that falls into the Sherloc evidence guidelines. The variant classification role is only to gather and apply the evidence; the evidence itself is what determines the final classification.

- How often are deletions/duplications (CNVs) detected in panel testing?

At Invitae, intragenic deletions and duplications (del/dups), or copy number variants (CNVs), are detected in approximately 10% of individuals with a clinically significant result (i.e., Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic variants). The fraction of positive individuals with del/dup findings vary by clinical area, ranging from 5% in Cardiology and 7% in Cancer to 39% in Neurology.

Learn more

- Download white paper for the most current data across clinical areas—Detecting deletions and duplications

- Read the Genetics in Medicine article to learn about Invitae’s experience with NGS-based del/dup detection —Prevalence and properties of intragenic copy-number variation in Mendelian disease genes.

If you would like to discuss estimates specific to your patient’s order, please contact our clinical team.

- Why is "Invitae" cited as a reference in the report?

Invitae uses information from individuals undergoing testing to help classify variants. If "Invitae" is cited as a reference in the report this may refer to individuals currently undergoing testing and/or historical internal observations.

- How does Invitae determine which transcript to use?

Some genes may undergo alternative splicing, a process that results in the generation of different protein variants from the same genetic sequence by altering the pattern of intron and exon elements joined by splicing to produce mRNA. The instructions for these alternative mRNA products are contained within the gene transcripts. For some genes, different transcripts are expressed in different tissues at different stages in development.

First, Invitae scientists review the available literature to find clinically relevant variants in a gene. Then, they compare the discovered variants with the available transcripts for each gene and select the transcript that captures the majority of clinically reported variants. To ensure that previously described clinically relevant variants aren't missed, we will report on several transcripts when there isn't a single transcript that captures all reported variants because of alternative splicing.

- Can Invitae classify a variant for me?

We do not provide classifications for variants that have not been formally evaluated by our report writing team. Our team of experts use Sherloc, our classification framework, to integrate prior curation, historical data, natural language processing-assisted literature searches, clinical information from the patient or family, laboratory metrics, and multiple quality control steps that we can only produce for variants detected in our lab.We routinely share our classifications with ClinVar, and we have described the Sherloc classification framework in detail in PMID: 28492532.

If you have specific questions about variants we have submitted to ClinVar, please contact us at clinconsult@invitae.com.

- What genome build does Invitae use?

Invitae uses genome assembly GRCh37.

- How are population allele frequency data used for variant classification?

General population allele frequencies – such as those made available by gnomAD – are invaluable for variant classification. As such, Invitae has developed an approach for evaluating population data that is more sophisticated than simply comparing allele frequencies against a single threshold.

How does Invitae calculate allele frequency values?

Typically, the evaluation of population data involves a very simple allele frequency (AF) calculation of a variant. However, this approach does not work well when comparing allele frequencies derived from cohorts of different sizes, such as those pervasive in gnomAD. For example, a variant in intronic or promoter regions may be represented by a cohort of a few thousand individuals, while a variant in the exonic region may be covered by a few hundred thousand individuals. Even if those two variants resulted in the same allele frequency, the precision of those frequency values will be vastly different. To account for this issue, assessment of population frequency is done by calculating the confidence intervals around the reported allele frequency.

How does Invitae evaluate allele frequency data for variant classification?

The American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines recommend that when “(an) allele frequency is greater than expected for a disorder,” it should be considered strong evidence for a benign classification (PMID: 25741868). Rather than draw arbitrary thresholds, we have developed two methods for empirically evaluating whether, and by how much, a variant allele frequency deviates from expectation.

In the first approach, we use a machine learning-based approach called Population Frequency Modeling. This method learns from the distribution of frequencies of known pathogenic and known benign variants, gene-by-gene, and quantitatively evaluates the probability of pathogenicity based on a given variant’s allele frequency. For more detail on Population Frequency Modeling and its clinical validation, please download the white paper below.

While Population Frequency Modeling is the preferred method, this apporach is limited only to genes where there are sufficiently large numbers of known pathogenic and known benign variants necessary for gene-level model validation. For genes where Population Frequency Modeling is not suitable, we still rely on the allele frequencies of known pathogenic variants to set expectations. However, in this second approach, genes are grouped based on the associated disease(s)’ mode-of-inheritance. Allele frequency thresholds to be used in variant classification are derived empirically based on a method previously described in PMID: 28166811.

Learn more

Download white paper—Population Frequency Modeling - How are CFTR poly T/TG variants classified?

Experiments clearly show that a T5 allele leads to the exclusion of exon 10 and the production of a non-functional protein (PMID: 7691356, 7684641, 10556281, 14685937, 216586497). In a mini-gene assay, exon 10 exclusion was 4% for the TG11-T5 allele, 10% for TG12-T5 and 18% for TG13-T5 (PMID: 10556281). The TG12-5T and TG13-5T alleles are reported to cause congenital absence of vas deferens (CAVD) in males and a non-classic form of cystic fibrosis (CF) when homozygous or present in trans with a second pathogenic CFTR mutation (PMID: 14685937). The TG11-T5 allele is reported to cause congenital bilateral absence of vas deferens (CBAVD) in males when present in trans with a second pathogenic CFTR mutation (PMID: 14685937). However, these individuals do not have symptoms of cystic fibrosis. When the 5T allele is found in trans with a severe CF mutation, the odds of disease are 30 times greater for TG12 and TG13 than for TG11 (PMID: 14685937). We classify the TG12-T5 and TG13-T5 alleles as pathogenic. The TG11-T5 allele is classified as pathogenic (low penetrance). Any alleles with T7 or T9 are classified benign and we do not include them in the primary report.

- Do you analyze and report the 5T and TG/T tract variants in CFTR?

For diagnostic CFTR testing, variants in the polymorphic TG/T tract are analyzed, interpreted, and reported if classified as “pathogenic,” “likely pathogenic,” or “variant of uncertain significance.” If present, 5T/TG variants classified as pathogenic are included in the report. The 7T, 9T, and other TG/T tract combinations, classified as benign, are not included in the primary report but are available upon request.

Historically, when we reported carrier screening results, when the 5T variant is present in conjunction with 11TG, 12TG, or 13TG, it is reported. We do not report the presence of 5T if it is in conjunction with any other TG tract variant (e.g., 10TG). A 5T variant is always associated with a specific number of TGs in the gene. Some TG numbers (e.g., 11, 12, 13) are known to be problematic (to different degrees), while others (e.g., 10) are not thought to be pathogenic.

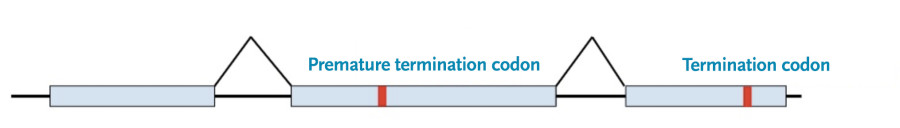

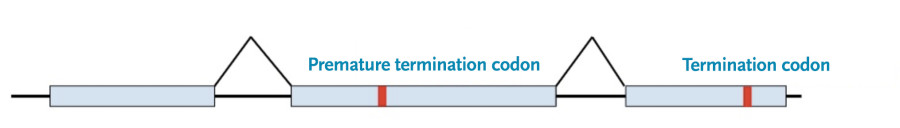

- Why are termination codons in the last exon reported as VUS?

Termination codons in the last exon are not pathogenic without additional evidence because they have a fundamentally different effect on the protein product than termination codons found in other exons.

To understand why we need to know how the cell makes protein products from RNA and the role that termination codons usually play in that process:

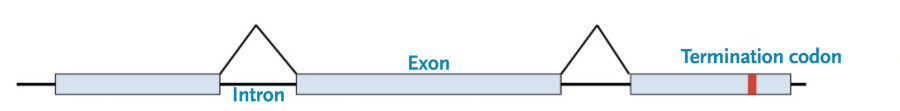

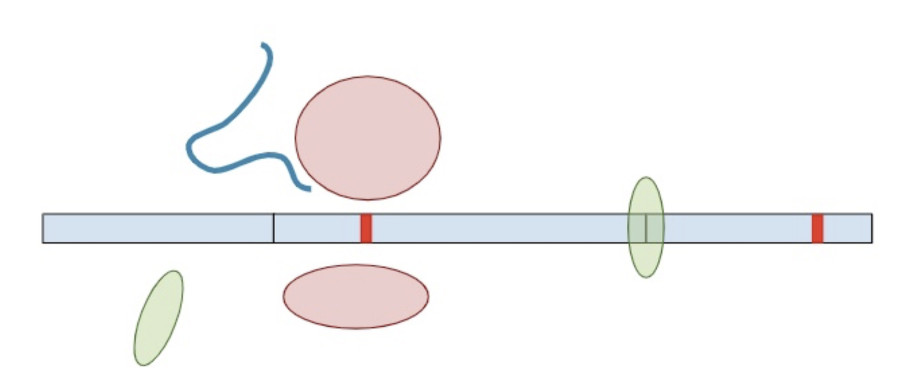

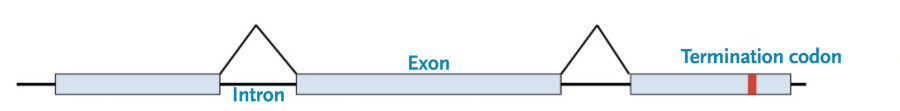

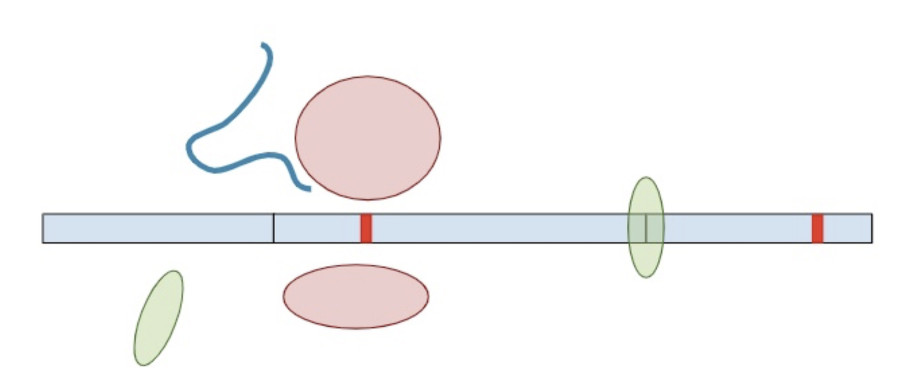

First, the cell copies the DNA into an initial messenger RNA molecule that contains both exons and introns.

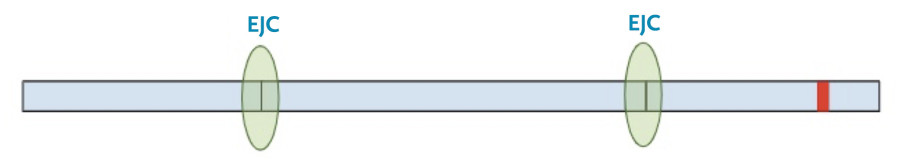

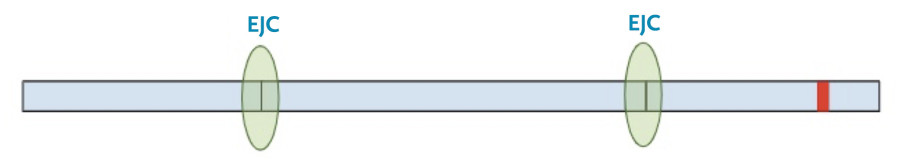

Next, the spliceosome complexes remove the introns leaving only the exons, with exon junction complexes (EJC) at the position of the original splice junction.

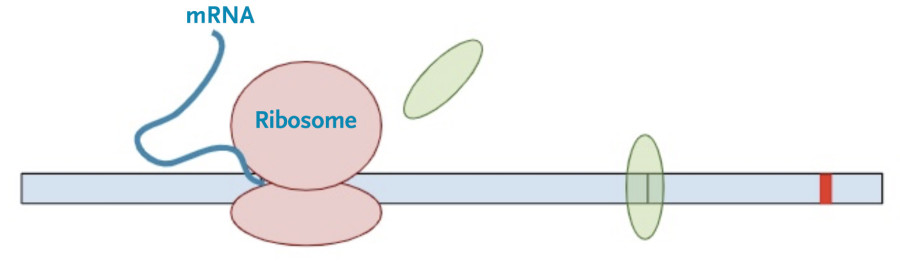

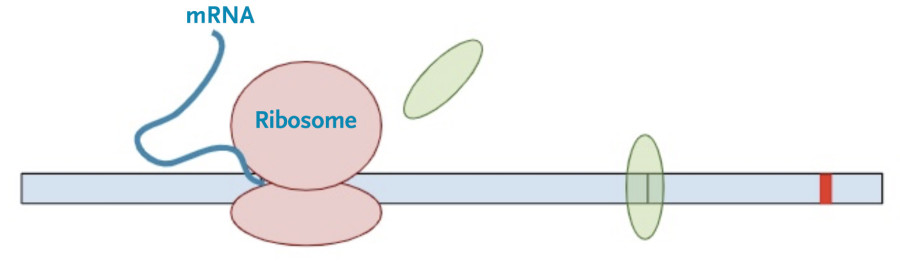

Then, the protein transcription machinery (ribosomes) starts translating the messenger RNA into protein. The process stops when the machinery reaches the termination codon. This is the signal that the protein transcription machinery uses to ‘know’ when to stop adding amino acids to the growing protein chain. Along the way, the protein transcription machinery also removes the exon-junction complexes from the RNA.

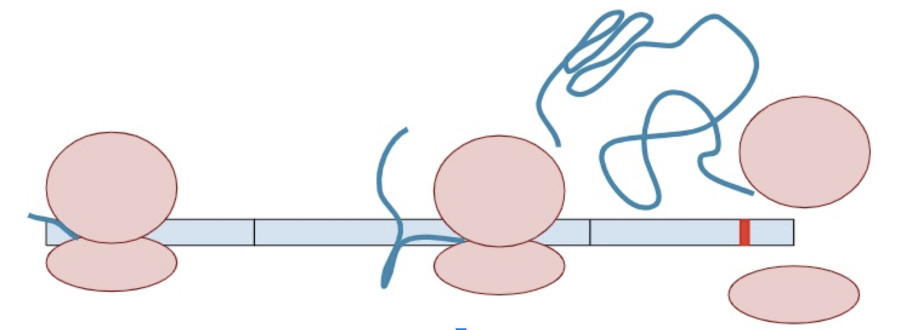

Once one copy of the protein product is made from the RNA, dozens, if not hundreds, of additional protein copies are made from that one molecule of RNA.

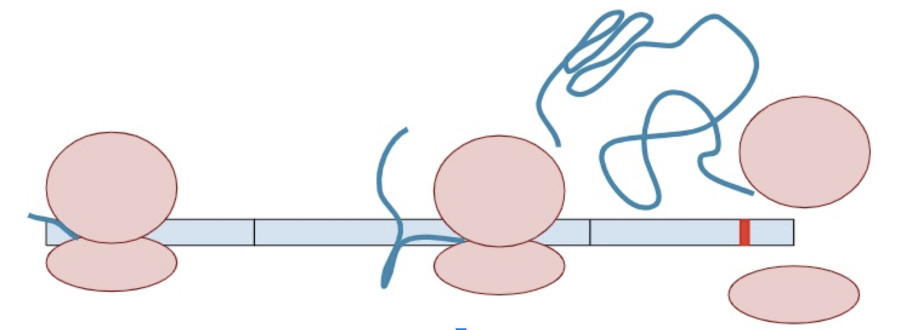

Sometimes, a variant creates a second termination codon earlier in the gene. This is known as a ‘premature’ terminal codon.

The RNA copy is made and spliced normally, leaving exon-junction complexes wherever splicing occurred.

In this situation, the protein transcription machinery stops when it reaches the premature termination codon instead of the original termination codon and at least one of the exon-junction complexes remains on the RNA.

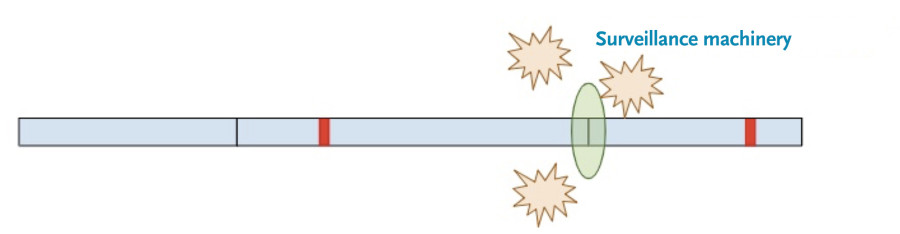

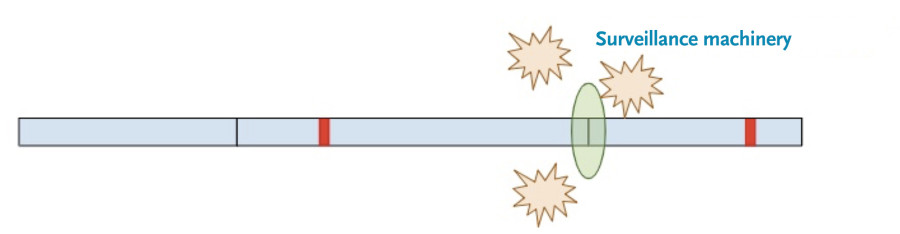

Now, a different process kicks in. Because exon-junction complexes should be removed during translation, any RNA molecules that still retain exon-junction complexes must have a premature termination codon. Specialized surveillance machinery is used to find these RNA molecules.

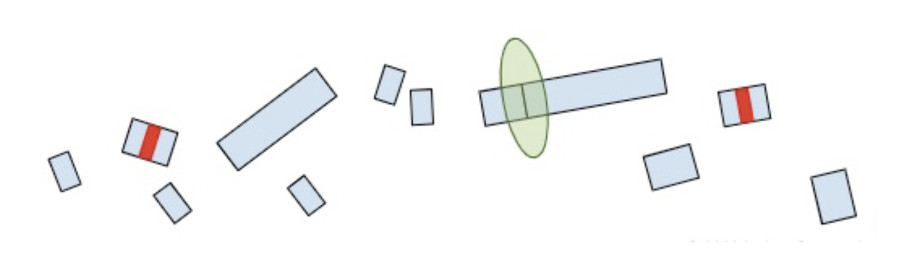

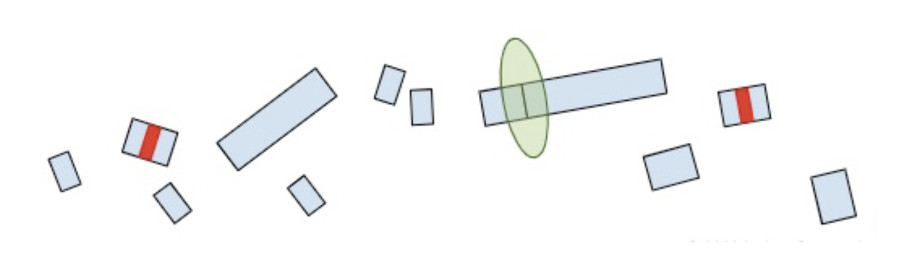

Once the machinery finds the RNA molecules, it breaks them down so that they don’t continue to create truncated protein products.

Now that we understand how the cell makes protein products from RNA and the role of termination codons, we can conclude our original question: “Why are termination codons in the last exon reported as VUS?”.

If the premature termination codon is found within the last exon, the RNA molecule will not retain any extra EJC’s so the surveillance machinery won’t be able to identify and break it down. As a result, the RNA will continue to create a protein product, except the product will be lacking whatever residues would have been present in the full-length of the protein. So while most premature termination codons that are positioned anywhere else in the gene will lead to a nearly complete loss of the protein product, premature termination codons in the last exon are more akin to a deletion of the end of the gene. Without additional clinical or functional evidence showing that the deleted amino acids are deleterious, premature truncations in the last exon are of uncertain significance.

- Why is this truncation in the second-to-last exon a VUS?

If a premature termination codon is created within the second-to-last exon and is very close to the end of that exon, the protein transcription machinery (ribosomes) will still remove the exon-junction complex that connects the second-to-last exon to the last exon ensuring that the RNA won’t be degraded by the surveillance machinery. We treat premature termination codons within the last 15 codons of the second-to-last exon in the same way as if they were in the last exon; they are of uncertain significance without additional evidence.

- What are pseudodeficiency alleles?

Pseudodeficiency alleles are DNA variants that can lead to false positive results on biochemical enzyme studies, but are not known to cause clinical symptoms or lead to disease. Enzyme studies cannot differentiate between true pathogenic variants and pseudodeficiency alleles, so these must be distinguished by molecular studies.

Enzyme studies measure enzyme activity, or the ability of an enzyme to convert a specific substrate to a product. The inability (or reduced ability) of an enzyme to catalyze this conversion can lead to disease. In a laboratory enzyme assay, synthetic substrates are commonly used instead of the substrate naturally found in the body. Pseudodeficiency alleles are known to impair an enzyme’s ability to convert this artificial substrate to product, which can lead to a false positive result on enzyme tests. Enzymes encoded by pseudodeficiency alleles can process natural substrate normally, or at a level that does not result in disease.

Why does Invitae report pseudodeficiency alleles?

Invitae reports pseudodeficiency alleles to help clinicians interpret abnormal biochemical results. Both diagnostic studies and large-scale screening programs (such as newborn screening, prenatal carrier screening, and Tay-Sachs carrier screening) frequently utilize enzyme studies to identify at-risk individuals, and false positive results are not uncommon. Molecular analysis can identify variants known to be pseudodeficiency alleles and is able to discriminate a true positive (abnormal) biochemical result from a false positive (abnormal) biochemical result.

Invitae reports pseudodeficiency alleles identified by sequencing in our results because these variants can provide an explanation for previous or future abnormal enzyme testing. This information can reassure the clinician and the patient that the patient is not considered to be affected with the respective disorder despite abnormal enzyme studies.

How common are pseudodeficiency alleles?

The overall incidence of pseudodeficiency alleles is unknown, but large-scale screening programs have found that approximately 2% of Ashkenazi Jewish individuals are carriers of a pseudodeficiency allele for Tay-Sachs disease (HEXA gene), while approximately 36% of the non-Ashkenazi population is a carrier for a HEXA pseudodeficiency allele (1). Approximately 3.9% of the healthy Japanese population is homozygous for a common glycogen storage disease: type II (Pompe disease; GAA gene) pseudodeficiency allele (2). Pseudodeficiency alleles have also been identified in metachromatic leukodystrophy (ARSA gene), mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) type 1 (also known as Hurler syndrome or Scheie syndrome; IDUA gene), GM1 gangliosidosis (GLB1 gene), Krabbe disease (GALC gene), Sandhoff disease (HEXB gene), Fabry disease (GLA gene), MPS type 7 (also known as Sly syndrome; GUSB gene) and fucosidosis (FUCA1 gene) (3). In addition, a pseudodeficiency allele has also been reported in a non-lysosomal storage disorder, tyrosinemia type I (FAH gene) (4).

Are pseudodeficiency alleles inherited?

These DNA changes are inherited just like any other genetic variant and can be passed to offspring. Individuals may be heterozygous, compound heterozygous, or homozygous for a pseudodeficiency allele.

Can two pseudodeficiency alleles in the same gene or a pseudodeficiency allele inherited with a known pathogenic allele in the same gene cause disease?

Based on currently available data, pseudodeficiency alleles are not thought to be associated with clinical symptoms. Many unaffected individuals with two pseudodeficiency alleles or a pathogenic allele and a pseudodeficiency allele have been identified in the population (data obtained from the nomAD database).

Can the presence of a pseudodeficiency allele in an affected individual with two pathogenic variants cause more severe disease?

At this time, there is no evidence showing a more severe clinical presentation in individuals with two pathogenic variants and one or more pseudodeficiency alleles.

References

1. Park NJ, Morgan C, Sharma R, et al. Pediatr Res. 2010;67(2):217-20.

2. Labrousse P, Chien YH, Pomponio RJ, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99(4):379-83.

3. Thomas GH. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54(6):934-40.

4. Rootwelt H, Brodtkorb E, Kvittingen EA. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55(6):1122-7. - Why is PKD1 not offered on the PKD panel?

PKD1 has a pseudogene issue that requires special steps to ensure variants we detect are specific to PKD1 (i.e., steps such as those we took for PMS2).

Scientific contribution

- How does Invitae share data, while also protecting patient privacy, to help advance genetic knowledge?

Invitae believes that knowledge is most valuable when it is shared. We currently submit all clinically reported variants, their classifications, and the evidence supporting their classifications to ClinVar—a public database of information on the relationships between genetic variation and human health. All data are shared in compliance with the HIPAA Privacy Rule, which protects the privacy of personal health information and requires that the data be stripped of any information that would allow individual patients to be identified. Learn more about how we protect patient privacy here.

Invitae is also one of 11 original members of the Gene Curation Coalition (GenCC), which maintains a public database on gene-disease relationships for more than 3,300 genes. Both public and private member organizations regularly submit de-identified data to the GenCC Database, allowing the coalition to evaluate the validity of the relationships and develop consistency in terminology for both evaluating and describing what role genes play in disease.

Sharing de-identified data on clinically reported variants and gene-disease relationships facilitates ongoing quality control for laboratories, detailed peer review of variant classifications and gene-disease interactions, and consensus classification by the global medical genetics community. The data can also be used to update variant classification guidelines and improve the overall quality of personalized medicine.

Learn more

- Read blog post—Leading with quality: Data sharing

- Read blog post—Is better patient care dependent on sharing data?

- Does Invitae conduct original research?

Invitae contributes to advancing the field of medical genetics by presenting its research findings at national and international conferences and by publishing original research articles, review articles, and invited commentaries in peer-reviewed journals.

Our medical geneticists, genetic counselors, and other experts regularly present at annual meetings of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, the American Society of Human Genetics, the National Society of Genetic Counselors, and many other professional organizations. We have also published more than 200 articles in distinguished journals such as the American Journal of Human Genetics, Genetics in Medicine, JAMA Network Open, JAMA Oncology, the Journal of Clinical Oncology, and journals specializing in molecular diagnosis, pediatrics, cardiology, and bioinformatics.

Invitae routinely collaborates with academic institutions, hospitals, and clinics to advance science in human genetics. For example, based in part on evidence published by Invitae and its collaborators, the American Society of Breast Cancer Surgeons updated one of its consensus guidelines in 2019 to recommend genetic testing for all patients with breast cancer rather than just those of a certain age and family history. We have also generated similar evidence in other areas of medicine, such as pediatric neurology and cardiology, suggesting that many patients with clinically actionable genetic variants are being overlooked. Our presence in the scientific and medical literature will continue to provide data like these to help shape evidence-based guidelines, impact clinical care, and improve access to comprehensive genetic testing services.

Learn more

- What professional education opportunities does Invitae provide?

Invitae’s goal of integrating genetic testing into mainstream medical care will require substantial efforts involving the education and training of medical professionals. As the landscape of clinical genomics rapidly expands, we are dedicated to helping genetic counselors, clinical geneticists, and non-genetics healthcare providers understand the cutting-edge advances in this field to provide the highest quality of patient care.

Continuing education

Invitae regularly hosts webinars to highlight the methods, research, and data behind our science and technology and to showcase best practices for integrating genetic information into patient care. In 2020, we launched our first webinar series approved for continuing education units (CEUs) by the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC).To register for upcoming webinars or view previously recorded webinars, please visit our webinars page.

Invitae is also proud to sponsor and help organize select conferences, educational sessions, and programs that further the genetics proficiency of medical professionals in our community. We accept proposals to fund these activities as well as to support the development of accredited continuing medical education (CME) content. To request financial support for an event, please reach out to your local Invitae representative. To request a speaker for your event or if you have CME-related questions or proposals, please contact us at medicaleducation@invitae.com.